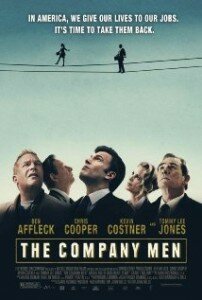

- The Company Men

- OPENING: 01/21/2011

- STUDIO: The Weinstein Company

- RUN TIME: 101 min

- ACCOMPLICES:

Trailer, Official Site

The Charge

In America, We Give Our Lives To Our Jobs. It’s Time To Take Them Back

Opening Statement

The Company Men opens with a man getting fired, and then slowly morphs into an episodic melodrama about life and the little things we take for granted.

Starring Ben Affleck (continuing his career resurgence) Tommy Lee Jones, Chris Cooper and Kevin Costner; John Wells’ film boasts a captivating presence, told with subtlety and grace typically lacking in mainstream Hollywood fair. I’m surprised there hasn’t been more awards recognition, especially on behalf of Jones and scene stealer Craig T. Nelson.

Facts of the Case

Bobby Walker (Affleck), a corporate big shot (in sales, no less) arrives at work one morning, after playing 18-holes of golf, and suddenly finds himself without a job. Turns out his uber-rich company took a hit during the recession. No problem, right? After all, he has plenty of credentials to land a similar job elsewhere.

Unfortunately, the economy is in the shitter and everyone from Walker’s boss, Gene McLary (Tommy Lee Jones), and McLary’s boss, James Salinger (Craig T. Nelson), are feeling the repercussions.

Bobby and his cohorts are suddenly burdened by a life of no income, and no credentials. One by one each must make the proper changes to ensure survival for themselves and their families.

The Evidence

In John Wells’ film, greed certainly is not good. Here, the corporate stooges, embodied with ham-fisted cruelty by Craig T. Nelson, defend their glamorous, wine n’ dine lifestyle with ruthless abandon. Nelson’s character must, at one point, choose between selling his newly furnished sky rise and laying off more of his own employees. Guess which one the schmuck chooses?

I say ‘schmuck’ with my tongue planted firmly in cheek. After all, Nelson’s Salinger remains a one-note evil doer, one with little regard to humanity. I imagine he’d kick a dog, whilst shoving old ladies on the street and then steal a nickel from a little girl if he had the chance. Do men like him really exist? At some point it would’ve been nice to get a closer look at the goings-on in his brain.

Of course I’m ruminating on a minor side character, one that gets precious little screen time, and even few speaking parts. And yet, Salinger’s presence dominates the film entire. His actions prod the film along in a non-discreet way. When a character dies and the obligatory funeral scene arrives, Salinger is noticeably lacking. Here is the first character in a long while whose presence is felt more when he is off-screen than on it. I was reminded of Skipper, a major character in Tennessee Williams’ Cat On a Hot Tin Roof. He never once appears on screen and yet his off screen actions (specifically his death) drive those of the performers. Salinger may be cartoon in nature, but he’s remarkable enough to justify the film taking some unbelievable steps to its foregone conclusion.

That doesn’t mean Affleck, Jones and company are any less remarkable, just overshadowed – but in a good way. Affleck portrays a man who no longer has control of his life. Everything he loved about the world–six-figure salaries, limos, company jets, golf at expensive resorts–has been replaced by an atypical lifestyle filled with hard work, little pay and familial affairs. So accustomed was he to his life that he takes it as an insult when his brother-in-law (Kevin Costner, sturdy as ever), a carpenter, generously offers him a job. “I don’t see myself pounding nails,” Bobby snarls. These are men who would rather commit suicide than endure the low-level ridicule of 60K (or less) jobs.

Wells’ film observes the downward spiral of Bobby, and those who suffer along with him. Many a set are decorated to show off the high-life these men and their families lost themselves to. Jones’ character behaves less like a man than a ghost, and it’s a testament to the veteran actor that he’s able to pull off such a quiet role, but still maintain a prominent presence. You sense his inner-turmoil by the way he stares mournfully, but respectfully, at Bobby during a brief lunch meeting and by the things he doesn’t say to his materialistic wife.

In fact, much of what makes The Company Men such a supremely well-crafted film is that it refuses to bark in your face. There’s more at work here than just a simple lesson in morals. Wells has constructed a true examination of ethics, rites of passage, etc. Not to mention a slightly disturbing bit of family dysfunction–namely how men must work to supply their spouses with money. An misogynistic undertone slithers beneath the surface; you can see it in those twin Christmas trees standing on either side of Gene’s front door–placed there by his plastic-model-of-a-wife, of course–and in the token corporate bitch (Maria Bello) who downsizes her fellow employees in a cold, calculating manner. Granted, Bobby’s wife (Rosemarie DeWitt) provides a likeable female character to root for; if there were others, then I sorely missed them.

Some may balk at the morality tale on display, and the oft-told coda of how money doesn’t buy happiness, but I found Wells’ film surprisingly refreshing, even monumental, particularly in these trying times. Finally a lesson for those of us who think big homes, big screen TVs and gold-plated China pave the road to contentment. I found it almost funny that all of these men–Bobby, Gene and their humility-stricken fellow employee Phil (Chris Cooper)–arrive home to houses full of non-essentials, none of which supply even the slightest bit of comfort, and instead only serve as a reminder of just how empty they truly are.

I know not all people with money are vain, but it’s telling of our times that a person will spend $16,500 on a casual dinner table, or complain about having to fly commercial, when half the country are losing their jobs. That doesn’t mean you have to sell your boat, or your nice Porsche for that matter, but there may come a day when the vain things of this world (even movies) no longer apply. The Company Men simply asks, “Can you live without them?”

Closing Statement

Carrying a refreshing message that caters to the times, John Wells’ The Company Men is an engaging, even heartfelt, look at the current economic recession.

The Verdict

8/10

8/10

0 comments ↓

There are no comments yet...Kick things off by filling out the form below.

Leave a Comment