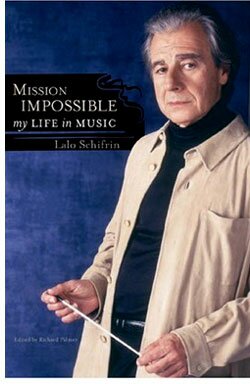

Judge Clark Douglas: We’re joined today by composer Lalo Schifrin. Mr. Schifrin has written many film scores over the course of his career, including music for such films as The Cincinnati Kid, Cool Hand Luke, Bullitt, Dirty Harry, Enter the Dragon, Tango, and the Rush Hour films. He has also written a great deal of music for television, including the memorable theme for Mission: Impossible. In addition, Mr. Schifrin has also worked extensively in the fields of jazz and classical composition. He has just released his autobiography, entitled Mission Impossible: My Life in Music. Lalo, thank you so much for taking the time to join us today.

Judge Clark Douglas: We’re joined today by composer Lalo Schifrin. Mr. Schifrin has written many film scores over the course of his career, including music for such films as The Cincinnati Kid, Cool Hand Luke, Bullitt, Dirty Harry, Enter the Dragon, Tango, and the Rush Hour films. He has also written a great deal of music for television, including the memorable theme for Mission: Impossible. In addition, Mr. Schifrin has also worked extensively in the fields of jazz and classical composition. He has just released his autobiography, entitled Mission Impossible: My Life in Music. Lalo, thank you so much for taking the time to join us today.

Lalo Schifrin: Oh, it is a pleasure.

CD: Let’s begin with your new autobiography. It’s a very enjoyable read, filled with fascinating stories and memories. Have you been collecting these and writing them down over the years, or did you decide to put together this book somewhat recently?

LS: No, I collected them in my mind, but didn’t put them down in paper until I started to write the book.

CD: It’s a really fascinating collection of anecdotes. How did you go about deciding how you wanted to put this book together?

LS: Well, I didn’t want to do it in biographical order. Sometimes, the chronological order can be boring. I’ve been involved, and I am still involved in films, television, jazz, classical, and all the celebrities I’ve met you can see in the book there. Many pictures, many photographs with many celebrities, all these you will see. Also, there’s a CD, a compilation of some of my music from the three fields. That made it easier, I didn’t have to tell a normal story. I just went by reminiscing, anecdotes… there are some funny anecdotes, and also some very serious stories… what I had to go through in my younger years before I left Argentina. There was a totalitarian government, Peron. All these stories, I thought they made interesting reading… drama on one hand, comedy on the other hand, and musical reminiscences.

CD: That’s one of the things that made it such an compelling reading experience for me. As you said, many biographies are written in a very linear fashion, and you almost know what to expect next if you know much about their life. In your book, there was something new, something fresh, or something surprising around every corner, and that really made it an interesting read.

LS: Thank you.

CD: You were born and raised in Argentina, and I understand that music was a pretty big part of your life from the very beginning. What was the experience of growing up in a musical family like?

LS: Well, you know, I didn’t even know there was anything else. My father, my uncles, my aunts, from my father’s side and my mother’s side… they were all professional musicians. My father was a concert master, he took me to a lot of rehearsals, concerts, performances, opera, ballet. For me, that was life.

CD: How old were you when you first began to appreciate the joys of music?

LS: Oh, I was very young, maybe five. The opera was very… I was attracted to opera to the point that I think it’s the reason I started to write music for films. I never studied. There are film and music school that teach you how to write music. I never studied that. But the influence of opera, which is a combination of storyline, visuals, staging, plus music… that was perhaps the best school I could have had. That’s what gave me the idea of coming to Hollywood to write music for films.

CD: Now before that, you met Dizzy Gillespie, who you talk about a good deal in your book. Can you tell us about how you originally met him, and what sort of impact he had on your musical career?

LS: Well, I was all ready familiar with him. When I became a teenager, I embraced jazz, heard records of jazz. I heard the music of Dizzy Gillespie, Charlie Parker (who wrote more than jazz), it was very complex. I was very attracted to it, since I was also studying harmony, composition, counterpoint… there was something about that music that I was attracted to. In fact, I did get a scholarship to study composition at the Paris Conservatory. I went to the Paris Conservatory to study at night, and the scholarship didn’t offer to much money, I still needed to make a living. So, I went to play jazz with some of the best European musicians in Paris, and even American musicians living in Paris. That was very good schooling for me in jazz. After Peron was overthrown, I wanted to go to Argentina to see my family. So I was going to go there for a few months. I missed my sister, my mother, my father, my friends, everybody. I was given an offer to have my own band, playing on my own television show and my own radio show. I was very young, just 24 years old, and it was a big temptation. Although I had my own apartment in Paris and I was very organized, working as an arranger and pianist… the temptation of having my own band… well, I wrote my arrangements immediately and all my charts and put together the best Argentinean jazz musicians. After a few months of performing there and being very successful with the Argentinean public, Dizzy Gillespie came with his state department band. It was a kind of musical ambassador from the United States. They went all over; to Asia, Europe, South America, and one of the points was Argentina. So, one night while they were there, I was asked to perform for them with my band. I did; I was conducting from the piano, Dizzy had me playing the piano. When we were finished, Dizzy asked me, “Did you write all those charts? Would you like to come to the United States?” I thought I was dreaming. So, it happened, that’s why I’m here in the United States.

CD: Wow. So, it was just a few years later when film and television music entered your life?

LS: Yes.

CD: Let’s talk for a moment about what is perhaps your most well-known composition, the theme for Mission: Impossible. In your book, you tell the story of the entertaining answer you gave when someone asked you why you wrote that theme in 5/4 time, so I won’t ask you that. But I would like to ask you… when you initially created the theme, did you have any sense that it would become as popular as it did?

LS: No, no. You know, there are no formulas for popularity. If I had the formula, everything I have ever written would be popular. (laughs). No, it was luck.

CD: That theme has really become a part of our pop culture, you hear it all over the place now. Did it have that kind of impact immediately, or is it something that seems to have grown over the years?

LS: It had an impact almost immediately. The problem was not the theme, the problem was the show. I did the pilot, and the pilot has to be sold to the network. It was sold, but the first year, it didn’t have big success. In fact, it was a danger that it might be dropped. The second year, the music was released on record. The show became very popular, and the music became very popular.

CD: In recent years, there have been three popular Mission: Impossible films, featuring new takes on your material by Danny Elfman, Hans Zimmer, and Michael Giacchino. What are your feelings on how your material was treated in those three scores?

LS: Very good. I was very pleased.

CD: Do you have a favorite among the three?

LS: Oh, the third one, by Michael Giacchino. It was… well, I liked all of them.

CD: Now, you also wrote another popular television theme for a show called Mannix.

LS: Yes, the same producer, Bruce Gellar.

CD: In your book, you talked about how you were working on a similar television show at the same time called Braddock. In fact, some of your music for Braddock was just released on a CD. What was it like working on those two very similar things at the same time.

LS: It was difficult. Braddock and Mannix… they were written in the same place, and they were picked by the networks because the computer appeared for the first time back in those years. They wanted detectives who worked with computers, Mannix and Braddock. They were very similar stories. I didn’t realize until I accepted Braddock that they were so similar. I had signed a contract before I saw the show; so I had to be sure that I wrote music absolutely different for each one. I don’t remember too much about the music I wrote for Braddock, but I remember that Bruce Gellar asked me to humanize Mannix. For the first two or three years, Mannix worked with computers, but then he became just a private eye. To humanize it, I wrote a kind of jazz waltz.

CD: Particularly back in the 1960s, you worked a lot in both film and television. Was one harder than they other, or did each have it’s own challenges and benefits.

LS: Oh, they both had their own challenges.

CD: The world of film music has changed a good deal over the years, and you’ve been writing over the past five decades. Do you find the experience of writing a film score to be more complicated and challenging than it was when you began or career, or is it the other way around?

LS: Well, the technology has changed, but the basic idea of making a contribution to a film musically is still the same.

CD: Hmm. It seems that orchestral music is slowly becoming less common in modern film scores, as a lot of movies are now employing a lot of electronic sound design. As someone who has been working on films for such a long time, what are your feelings on the current state of film music?

LS: Oh, you cannot say it like that. It’s not a current state. Scores are like fingerprints. Each film has it’s own music. Some are completely electronic, some are what I call electroacoustic, and some are symphonic. We cannot make a generalization of that.

CD: That brings up something I’ve been wanting to ask you about. Throughout your career, there seems to have been a fascination with fusing unusual musical elements together. This can perhaps be most explicitly heard in your collection of Jazz Meets the Symphony recordings, in which you blend notable classical works with jazz compositions. When did you develop a taste for that sort of musical experimentation?

LS: Oh, always! In fact, one of the reasons I came to Hollywood was that I could develop the idea of jazz meets the symphony. In Bullitt, Dirty Harry, all these scores that I wrote for films in which I could combine elements. In Cool Hand Luke it was bluegrass instead of jazz, but always with the symphony around. Even in Mission: Impossible and in Mannix, I had a symphony orchestra surround a smaller group. This was something that always attracted me. Finally, I decided to do a series of recordings. I did six recordings of Jazz Meets the Symphony, and I’m working on a seventh.

CD: Wonderful! Of course, those are pretty critically acclaimed works now. Were there ever points in your career when you tried some of this experimental stuff that wasn’t as well-received, when someone was telling you, “No, you shouldn’t mix these two things”?

LS: Well, I’d like to answer your question… actually, it’s two questions. First of all, I do not experiment. I don’t want to sound too arrogant… but they once asked Picasso, the great painter, “What are you looking for?” Picasso said, “I’m not looking for something, I found it.” I understand that because the same thing happens to me. I was born in classical music, assimilated jazz, and never understood why there had to be differences between the two. Both are good music. At the beginning, well, it was difficult. But the musicians in the symphony orchestra, they love it. The jazz musicians also love it because they feel great inspiration from that. The public took a little longer, because it was too new, but it’s being accepted now. I’m about to go to Paris to do Jazz Meets the Symphony, and I did one recently in London.

CD: Great. Over the course of your career, you’ve written music for a lot of different films and television shows. Is there one experience that stands out as being the most satisfying to you personally?

LS: Perhaps Cool Hand Luke. I liked the story, I liked the director… and also Dirty Harry. Different films altogether, but I like both very much.

CD: It’s interesting that you point out those two. I think both Dirty Harry and Cool Hand Luke… arguably two of the definitive iconic films of Paul Newman and Clint Eastwood; two roles that a lot of people really remember them for. Also, Steve McQueen in Bullitt and The Cincinatti Kid.

LS: Yes, The Cincinatti Kid. The title song was sung by Ray Charles, so yeah, I worked with Ray Charles. It was very nice, all of these experiences were very nice.

CD: You’ve worked on a couple of film franchises in your career… in the 1970s and 1980s, you wrote music for four of the five Dirty Harry films, and in recent years you’ve scored all three Rush Hour films. How do you feel about scoring sequels… is your approach considerably different when you’re working with familiar material rather than creating something entirely new?

LS: Well, the advantage is that the themes are all ready written. The challenge is that you have to adapt those themes for new situations. That’s a challenge, but I welcome challenges.

CD: Looking ahead to the rest of your career… is there still anything you haven’t tried yet that you would really love to do; a dream project of yours?

LS: My wife says, “Be careful what you dream, or it’s going to happen.” Right now I’m in the jazz music symphony. You know, a house is built brick by brick. So I don’t even know where this is taking me, but it’s always a journey. If you can see the line in my book from my life in Argentina to Paris, coming back, Dizzy Gillespie, coming to New York, working for a record company that was a subsidiary of MGM Records, and MGM was part of MGM, Inc., which was then the biggest film studio in the world. Because of the success I had with the subsidiary company, Verve, they invited me to come to Hollywood, and I started my career there. You can see the whole thing is a line. In retrospect, I didn’t plan it that way. You known, there was an Argentinean poet who said, “Fate and luck are synonymous.” I’ve been lucky, and that determined my fate, my destiny… so far.

CD: Well, Mr. Schifrin, you’ve certainly given us a great deal of wonderful music over the years, and I certainly look forward to anything you do as you head into the future. I also want to thank you for taking the time to join us today and share your thoughts with us.

LS: Well, thank you very much. I appreciate your invitation. For you, I would like to take the opportunity to say hello to all of your listeners and send my best wishes to everybody, you included.

For More Information:

Visit Mr. Schifrin’s official site ( schifrin.com )

Listen to Clark’s musical tribute to Lalo ( The Sounds and Sights of Cinema (09/02/08) )

Read Lalo’s autobiography Mission Impossible: My Life in Music (amazon.com)

Hear Lalo’s Jazz Meets the Symphony CD collection (amazon.com)

1 comment so far ↓

Nice interview with a legend, Clark. I loved your podcast compilation. Mr. Schifrin’s name didn’t come to mind so readily for me, but so many of his film scores are instantly recognizable. The selections you chose helped me to identify his particular style and appreciate how it has evolved over the decades. I won’t forget his name again.

Leave a Comment